MLK Week Highlights Community Voices, Past and Present

MLK Week Highlights Community Voices, Past and Present

Students and others describe what MLK means to them, learn the history of a black student group, and more.

(Images from MLK-week programming held on Tuesday and Wednesday. Source: The Spectator)

What does Martin Luther King, Jr. mean to you? This was the question asked of ten students, faculty, and community members at the annual Reflections Dinner hosted by Washington and Lee University’s Office of Inclusion and Engagement (OIE) on Wednesday, January 17, 2024.

The catered dinner in Evans Hall was moderated by Dr. Leslie Wingard Cunningham, the associate provost for faculty development. Cunningham, who began working at W&L last year, applauded the college for their week-long celebration of the life and legacy of Dr. King.

Cunningham first introduced Rev. Eric Anderson, pastor of Union Baptist Church in Glasgow.

(Schedule of speakers provided to participants at Wednesday’s Reflections Dinner. Source: The Spectator)

Drawing from King’s February 4, 1968 sermon, Anderson offered a definition of greatness that challenged his initial understanding of the term while growing up in Roanoke, Virginia. “I thought I was great because I was in the top of my graduating class and because I was accepted to all the colleges I applied to,” he said. “But I realized quickly that I didn’t understand what greatness really was.”

Anderson said that King understood greatness as living a life of service. “Everybody in this room can be great, because everybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve,” he emphasized, quoting King, “you only need a heart full of grace and a soul generated by love.”

Atiba de Souza, ‘26, reflected on King’s ability to find inspiration in past achievements at a time of crisis and oppression. “Our country has fallen in a space of incredible divisiveness and polarization. People care more about aligning with their party lines and party goals than what is right.”

Such attitudes, Souza says, preclude students, politicians, and others from civil discourse and positive change. “If we cannot put our pride aside and at least open our minds to hear opposing thoughts, our country will not only cease to make progress, but we will begin to backtrack.”

Warning against tunnelvision, Souza stated that “diverse thought is what drives innovation and real, tangible change that King fought so hard for. … We must look to see how our background makes us more similar than different.”

Laura Murambadoro, ‘26, spoke about the difficulty she and her family faced moving from Zimbabwe to Kansas when she was ten. “There was always the pervasive issue of racism,” which Murambadoro says made her “realize a lot about not being received well by people who were not people of color.”

Coming to W&L and hearing racist remarks right in front of her, Murambadoro said “there has been a plethora of experiences … that genuinely had left me confused about my place in my community and even about my own identity.”

While Murambadoro acknowledged that these experiences are “in my mind, pretty much all the time, this holiday and how we celebrate it really allows me to reflect … and not let what we learn from Dr. King go to waste.”

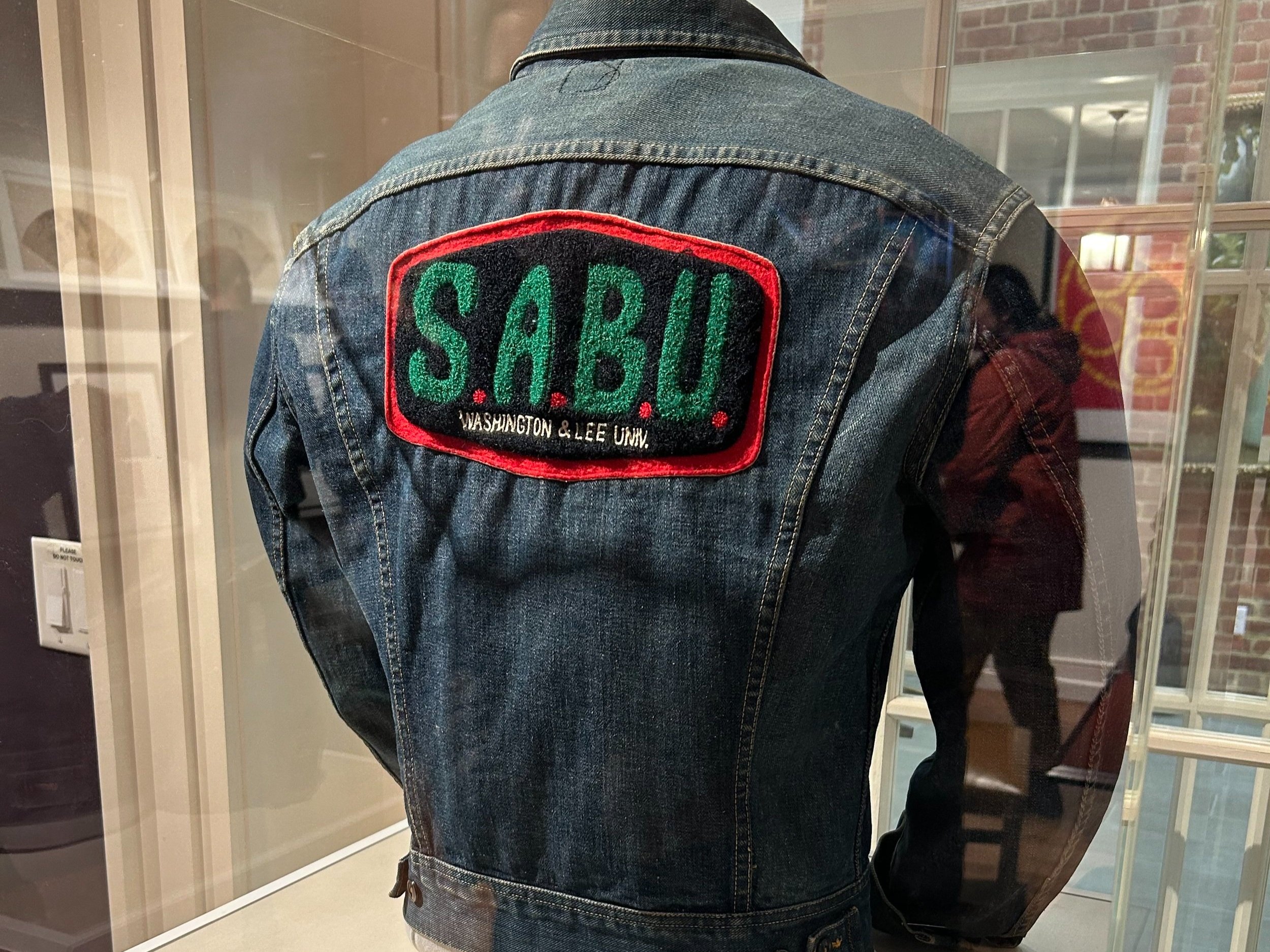

Serving as president of the Student Association for Black Unity (SABU), Murambadoro said she is especially grateful to have a community she can serve. She is also encouraged by King’s message of love and faith. “When the Lord is on your side, absolutely no one can stop you or change the impact that you were meant to make.”

Dr. Ayesha Kelly, a general surgeon in Lexington, focused her reflection on the fight to end segregation and inequality in health care. Sharing multiple historical accounts — many from her own family — Kelly explained how segregation resulted in substandard hospital conditionals and medical care for black people, who frequently could not be treated inside their community and who lacked the attention and funding provided to white patients.

(Dr. Ayesha Kelly, one of several Reflections speakers, talks in Evans Hall. Source: The Spectator)

Both Kelly and a later speaker — Col. John Young of Virginia Military Institute (VMI) — quoted King’s speech at the 1955 Medical Committee for Human Rights: “Of all forms of inequality, injustice in healthcare is the most shocking and the most inhumane.”

“King demand[ed] equality in not just schools and housing, but also healthcare. And that’s important to me because we don’t talk about all the aspects of segregation that touched people’s lives.”

Kelly recognized that her success owes to the work of Civil Rights leaders like King, as well as “local heroes” and physicians, “who fight to improve the world around them in their own communities.”

Other speakers included Executive Committee President Martha Ernest, ‘24, Jasmine Cooper, ‘24L, VMI cadet Mark Shelton, and Isra El-Beshir, the Director of Museums at W&L.

Singer Ana Montano Martinez, ‘25, and violinist Hannah Nolton, ‘25, performed Ben King’s 1961 song, Stand By Me, which they felt reflected King’s values of “togetherness and resilience.”

Other MLK-week events included a keynote address by Keisha Lance Bottoms, the screening of Till (2022), an African Society fashion and dance show, a concert, a basketball tournament, and a museum presentation that highlighted the experiences of the first black students who attended W&L beginning in the late-1960s. Both that event and the basketball tournament were sponsored by SABU, which was established in 1971.

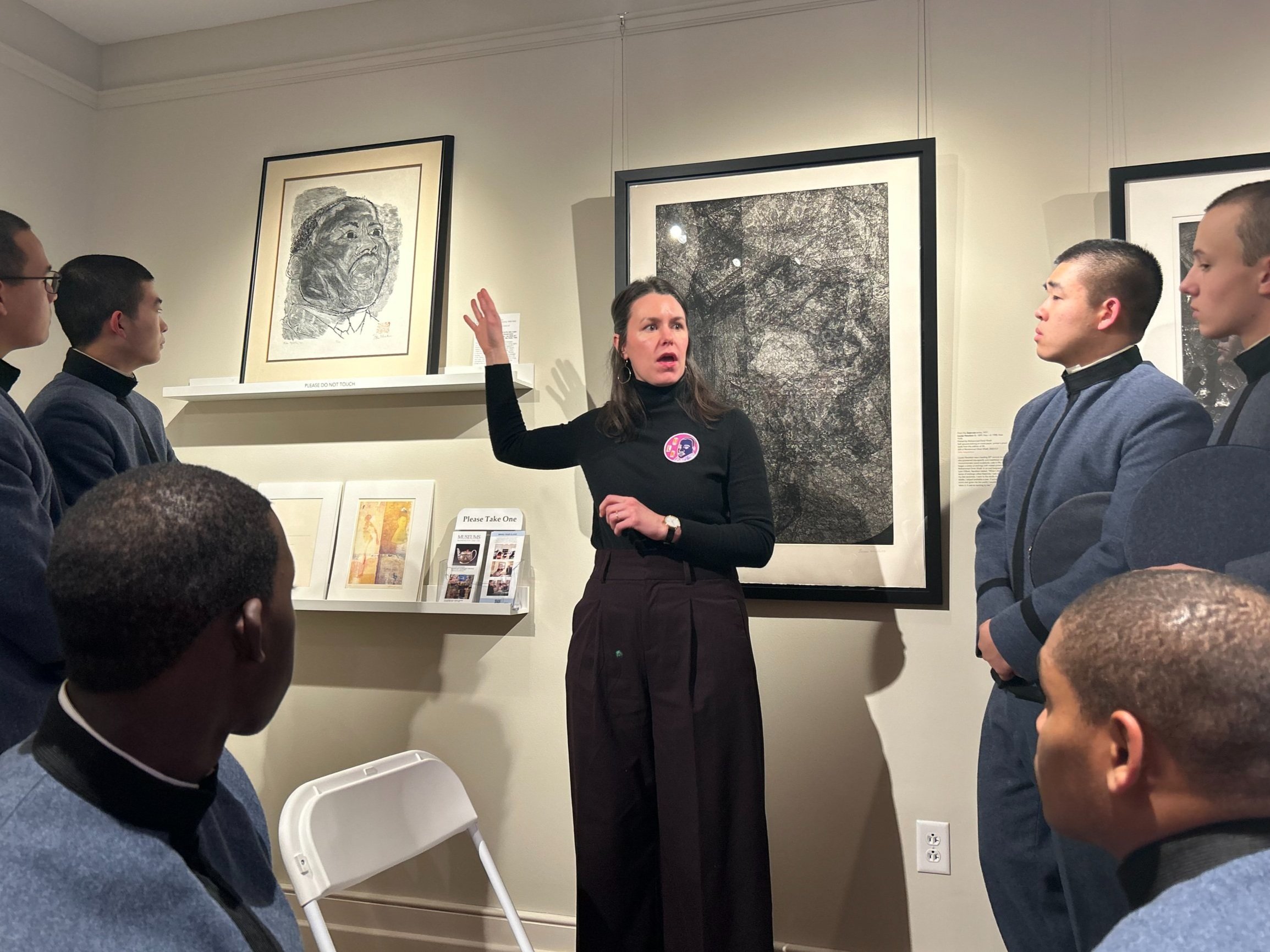

A handful of W&L students, faculty, and administrators attended the museum presentation on Tuesday, January 17. They were joined during the Q&A session by the late arrival of a couple dozen VMI cadets, who asked several questions about the history of SABU and desegregation at W&L.

The presentation revolved around the Museum’s recent acquisition of a denim jacket designed by SABU member William Hill, ‘74, ‘77L. The jacket, whose logo mimics the Pan-African flag, became an important symbol for black students on campus in the 1970s. The jacket, as well as a print of Martin Luther King, Jr. and a ceramic vase featuring a kneeling Colin Kaepernick, are currently on view in the Reeves Museum of Ceramics.

Also last week, Students for Historical Preservation (SHP) collaborated with W&L Special Collections and Archives in showcasing letters and other documents that share Dr. King’s connection to W&L. Of particular note was King’s 1967 letter declining an invitation to speak to the University Christian Association after his first invitation was rescinded by the university trustees five years prior.

SHP plans to discuss that story and W&L’s reaction to the Civil Rights Movement in further depth at their next meeting on January 28.