Who Deserves Reparations? A History of Sierra Leone

Who Deserves Reparations? A History of Sierra Leone

Though Sierra Leone means little to most Americans, Americans played a significant part in impoverishing western Africa.

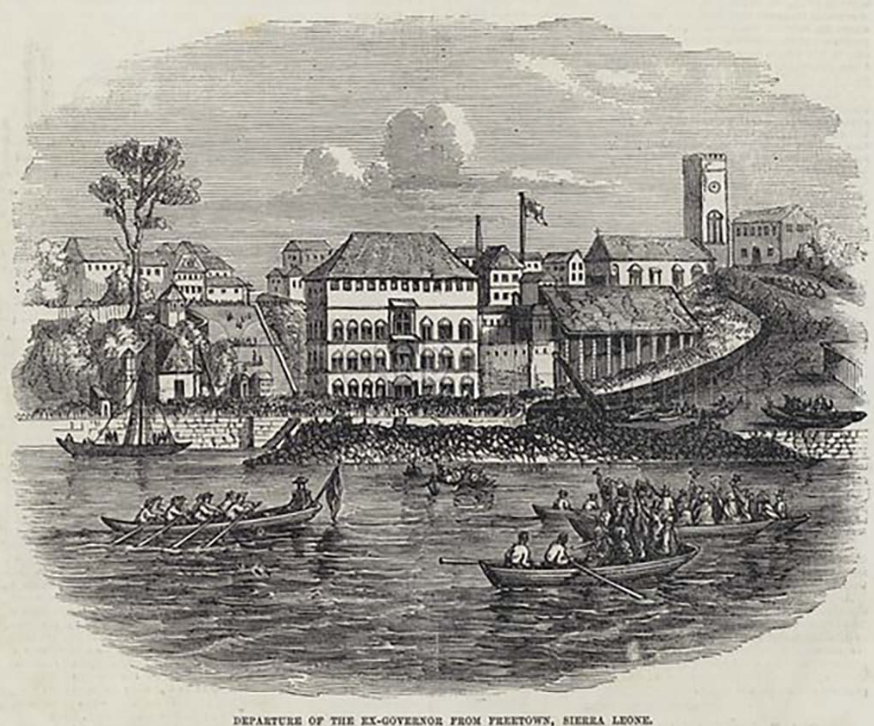

(Freetown, Sierra Leone. December 23, 1854. Public Domain Image)

Progressive activists continue to demand reparations for black Americans, attributing economic inequality to centuries-long policies that began with the transatlantic slave trade. There is no denying that Jim Crow and the American legal system oppressed the descendants of enslaved Africans. But there are other descendants whose ancestors were forced from the continent long before abolition and the Civil Rights Movement began to redress racial injustice in America.

Many of these men, women, and children were sent to Liberia beginning in the 1820s. Others were sent to Sierra Leone decades before that, courtesy of British promises to “liberate” black loyalists who fought against American patriots. Though the Founding Fathers won, their ideas of equality and self-advancement — eventually expanded to all citizens by leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr. — did not reach western Africa. Recognizing these inequitable conditions of early Sierra Leone suggests that if any descendants of African slaves deserve reparations, it is those whose forgotten ancestors settled what today ranks as one of the poorest countries on Earth.

Britain dispatched the first wave of black settlers to the colony of Sierra Leone on April 9, 1787. But London had already been using western Africa as an escape valve for urban social crises for two decades.

Britain’s first African colony — Senegambia — had become a disease-ridden failure within two years of its 1765 founding. British mortality was too high to continue sending redcoats, and Governor Charles O’Hara refused to enlist local Africans. What was modeled after the American colonies quickly became a solution to London’s growing prisoner population, as government officials supposed that criminals would prefer to be shipped to a west-African garrison instead of walking to the English gallows.

In reality, there was not much of a difference between the two. By 1787, humanitarian and practical concerns led the crown to redirect its convict transportation scheme to the more hospitable (and less diseased) region of Botany Bay, Australia.

Too harsh for England’s white convicts, western Africa became a convenient “solution” to another London problem: the “Black Poor.” Established in 1786, The Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor began by offering bread and employment to London’s indigent blacks. But believing that blacks could not exceed in England, the Committee turned to Henry Smeathman’s Plan of a Settlement to be made near Sierra Leone (1786).

Nearly 700 Black Poor signed up, though only about 440 people (including 70 poor, white women) set sail in April for the “Province of Freedom,” where “they could become architects of their own destiny.” The rough voyage killed 96 passengers before arriving at “Granville Town” on May 15, 1787. But the ensuing two years were worse: nearly one-third of the settlers died of disease. Many were captured by local tribes or white slavers, and some even worked at the slave-trading “factory” on Bunce Island. Disputes with the Temne tribe in 1789 led to the entire settlement being torched.

Five-hundred Nova Scotian households settled in the reestablished colony in 1792. They constituted 90% of the colony’s total population. Most of these former slaves had fought against the patriots during the revolution and had lived in Nova Scotia for less than a decade. Lord Dunmore had promised them freedom, but British officials decided that sending them “back” to Africa would be more advantageous to black health and mobility, and more profitable for the Empire.

One such veteran and settler was Harry Washington, an enslaved African whom future President George Washington purchased in 1763. Harry tried to escape in 1771 and succeeded in 1776. He served in Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment (among others) and may have helped besiege Charleston, South Carolina. He went to Birchtown, Nova Scotia in 1783 before sailing to Sierra Leone.

But Sierra Leone did not offer prosperity to men like Harry. Protesting tax policy in 1800, Harry and many others revolted against the British. The settlers lost and Harry was exiled into Sierra Leone’s uncolonized interior. He died soon after.

Even those who remained loyal to the crown suffered, as land distribution became increasingly inequitable. British intellectuals — like Granville Sharp — had originally hoped to create a self-governing, black yeomen society where every family farmed their own land.

The official land distribution policy for Nova Scotian settlers was 4 acres for every adult male, 2 for every female, and 1 for every child. In practice, this resulted in a mean of 5.2 acres per household. But by 1800 the household mean had decreased to 1.33 acres. And by 1831, land inequality had skyrocketed: 1% of the population received 8.7% of all distributed land and nearly 10% of the population received no land at all.

One primary reason for this inegalitarian change was that the British wanted to promote commercial agriculture to support the Empire. To do so, they allowed landowners in fertile regions to acquire more land, while unskilled laborers and carpenters received far less.

Sierra Leone clearly had humanitarian underpinnings. But more than anything, the colony was a convenient and economically-motivated solution to one of many internal British crises. Britain controlled Sierra Leone until 1961, though they hardly provided for its citizens. Since then, the state has endured a myriad of conflicts which continue to demand economic growth.

But the burden of responsibility falls on more than the British. Americans should recognize Sierra Leone’s connection to our Revolution. Harry Washington was not alone, and his fight for independence is as admirable as his former master’s. The question becomes how we can help remember the legacy of those early settlers. While talking about Harry is a start, it is better to help his descendants achieve what he never could: self-governance and social mobility.

America and Britain should begin a transatlantic discussion on whether reparations would give Sierra Leoneans the economic mobility they were falsely promised over two hundred years ago. Reparations might not be the right solution. Or maybe the over-politicized term is the issue. But it’s time to at least start the conversation, because for too long we have cast the indigent away under the pretense that they could become architects of their own destiny.

[This op-ed was written for Professor Mikki Brock’s History of Poverty in Britain course in Winter 2024.]

[The opinions expressed in this magazine are the author's own and do not reflect the official policy or position of The Spectator, or any students or other contributors associated with the magazine. It is the intention of The Spectator to promote student thought and civil discourse, and it is our hope to maintain that civility in all discussions.]