“Book Ban” Debate Arises at Local Middle School

“Book Ban” Debate Arises at Local Middle School

A teacher’s letter causes the removal of a racy graphic novel from Lylburn Downing Middle School.

Publishers Weekly describes Kiss Number 8 — written by Colleen AF Venable and illustrated by Ellen T. Crenshaw — as a “queer coming-of-age story that earns its powerful emotional impact.”

Lizzy Braman, a local fourth-grade teacher and mother of seven, claims that that 2019 graphic novel “focus[es] on sexuality discussed in graphic and degrading ways, with complete disregard for the value of any child’s innocence.”

Some Rockbridge County residents and educators have since disputed Braman’s claims — as explored later in this article — while others have celebrated her critical description.

The book, which was a finalist for two awards and a contender for others in 2020, has earned its place among contested LGBTQ titles. Although not included among the 13 most challenged books of 2022, Kiss Number 8 has been removed from multiple Texas school districts and helped prompt voters to withhold funding from a Michigan public library last year.

As of this month, that same text has been removed from another school, this time in Lexington, Virginia.

The initial call to remove the book

In a September 10 open letter, Braman noted that she had recently become “aware of the contents” of Kiss Number 8, a book then available in the “Young Adult” section of the Lylburn Downing Middle School (LDMS) Library. Braman’s letter has since gained attention in Rockbridge County.

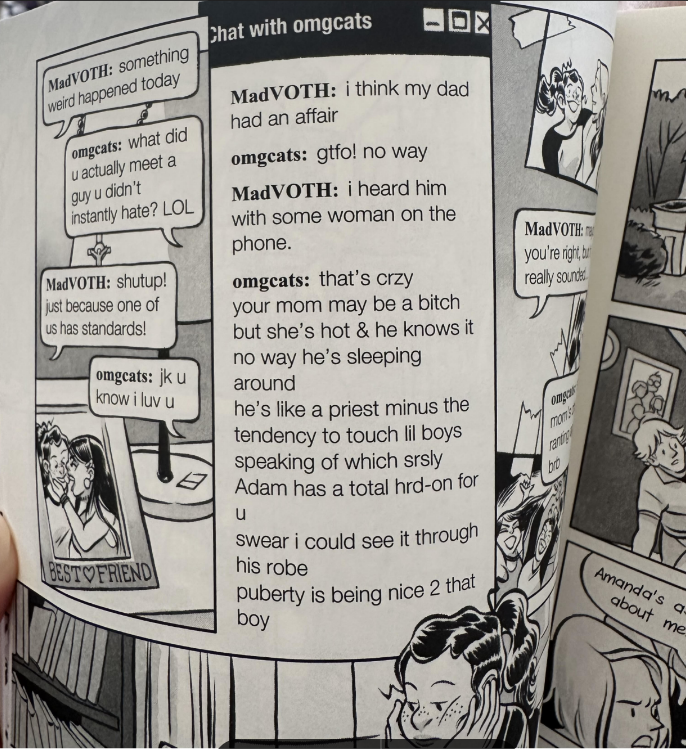

“With an extraordinarily heavy heart, I want to share these images with you [see below images] because our children have been exposed to them in school, and I believe you have the right to know about them[,]” Braman said.

“I think it is wrong, I want it stopped, and your help is needed[,]” Braman continued, calling for readers to attend the Lexington City School (LCS) Board meeting on October 3 at 5:30 PM.

The letter’s subsequent two-and-a-half pages clarified Braman’s stance on sexually explicit material, the ways in which she thinks public officials ought to evaluate young adult literature, and the protection she believes ought to be afforded to Christian beliefs.

“I am not here to judge any person’s gender or sexuality choices,” Braman said, “but I also do not give teachers license to educate my child so cheaply on gender choices, sexuality, or sex.”

“I understand that there needs to be health and development classes, taught in moderation with stated curriculum and parental warning[,]” Braman continued. “These books in the library, however, include graphic sexual language, concepts, and choices which I believe should be private and are appropriate considerations for children beyond the middle school age.”

“Anyone that chooses to offer information that ‘explores’ sexuality, in such detail, with my child at this age is grooming them for a life that I do not intend[,]” the letter states.

“Significant public funds have been used in recent years to purchase a huge quantity of books without any oversight[,]” the letter alleges. “Orders went directly from librarian, to secretary, to purchase. Even if policies change, those books are still in the library now.”

An August 2022 letter signed by LDMS librarian Theresa Bridge informed parents that a new policy was implemented to label “YA (Young Adult) titles” — as defined by the American Library Association (ALA) and the American Association of School Librarians (AASL) — with yellow and pink stickers on the spine.

According to Bridge, “YA titles account for approximately 40-45% of [LDMS’] entire fiction collection, which offers a nice balance to the 75% of our students who are technically ‘young adults.’”

“Materials deemed YA include mature topics/themes/concepts/content. Many class sets that teachers may use also have a YA label[,]” Bridge said.

And while “[a]ll library resources are currently available to all students,” Bridge noted that parents may “submit a letter in writing to the school librarian” if they “wish for [their] child(ren) to refrain from accessing YA materials in the LDMS library[.]”

In her recent letter, Braman criticized this policy, claiming that it “developed after years of parental complaint and management consideration, [but] has not prevented age-inappropriate material from being seen by students that did not actually check out the books themselves. Children who did not check out Kiss Number 8 (and were not actively trying to see inside it), were exposed to its contents in school by other students reading it openly in front of them in classrooms. The system of safeguarding is not functioning[,]” Braman wrote.

Continuing her letter, Braman disputes the notion that removing Kiss Number 8 is the same as “banning” a book.

“Do we have to ‘ban’ a book that is simply appropriate for an older audience? Do we really have to come up with a list of all the adult literature in the world to ‘ban’ from our age-specific library?” she asked.

For Braman, the defense of Kiss Number 8 and its inclusion in the library to begin with was and is inexcusable.

“Professional judgment should have dictated that this book is inappropriate for middle school children and unworthy of public funds to purchase for children…Therefore, we also falter in our trust of the school to administer systems that guide or protect even the most basic level of innocence in our children[,]” the letter continues.

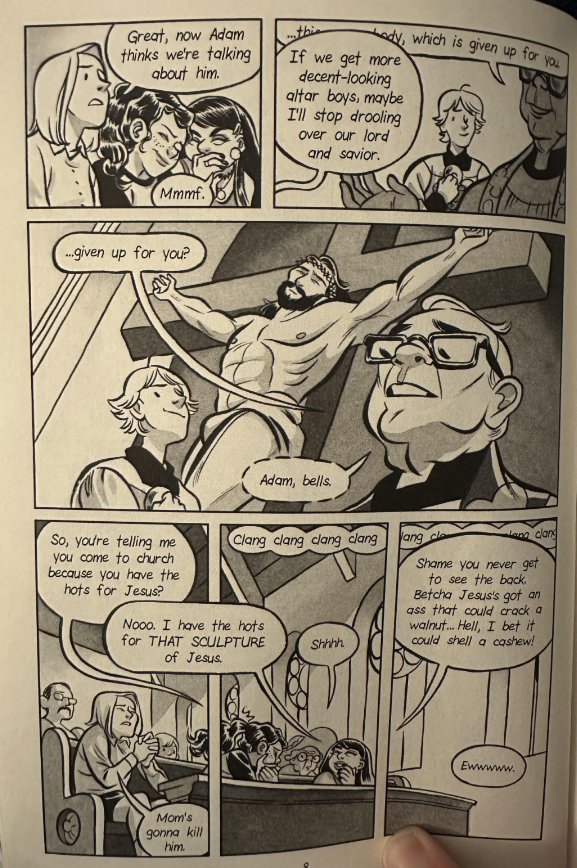

Braman then called for “all people of faith to stand against this debasement of my religious symbol and reality[,]” referring to the sexualization of Jesus Christ in Kiss Number 8.

“I am a Christian and I know we don’t all agree when it comes to religion[,] Braman declared. “But just because my beliefs and values are traditional, does not mean they don’t deserve acceptance and protection too.”

The letter concluded with seven requests to the LCS School Board.

The first request, which was subsequently amended, asked that Kiss Number 8 be removed from the LDMS library. Following its removal last week, the request now states, “would you please ensure that this decision does not get reversed?”

Other requests include to “investigate how this resource, and others like it, were admitted

into our middle school” and to “organize and facilitate an open review of the books currently in the library[.]”

The letter also asked for “an open review of the process by which public funds will be spent in the library” and that the board “organize and facilitate regular library open houses, such that parents may come in and see for themselves the books that are actually available to their children.”

Debate over the book ensues

While Braman’s letter has not received unanimous support, it has kindled an interest among both liberal and conservative community members to attend the upcoming LCS School Board meeting.

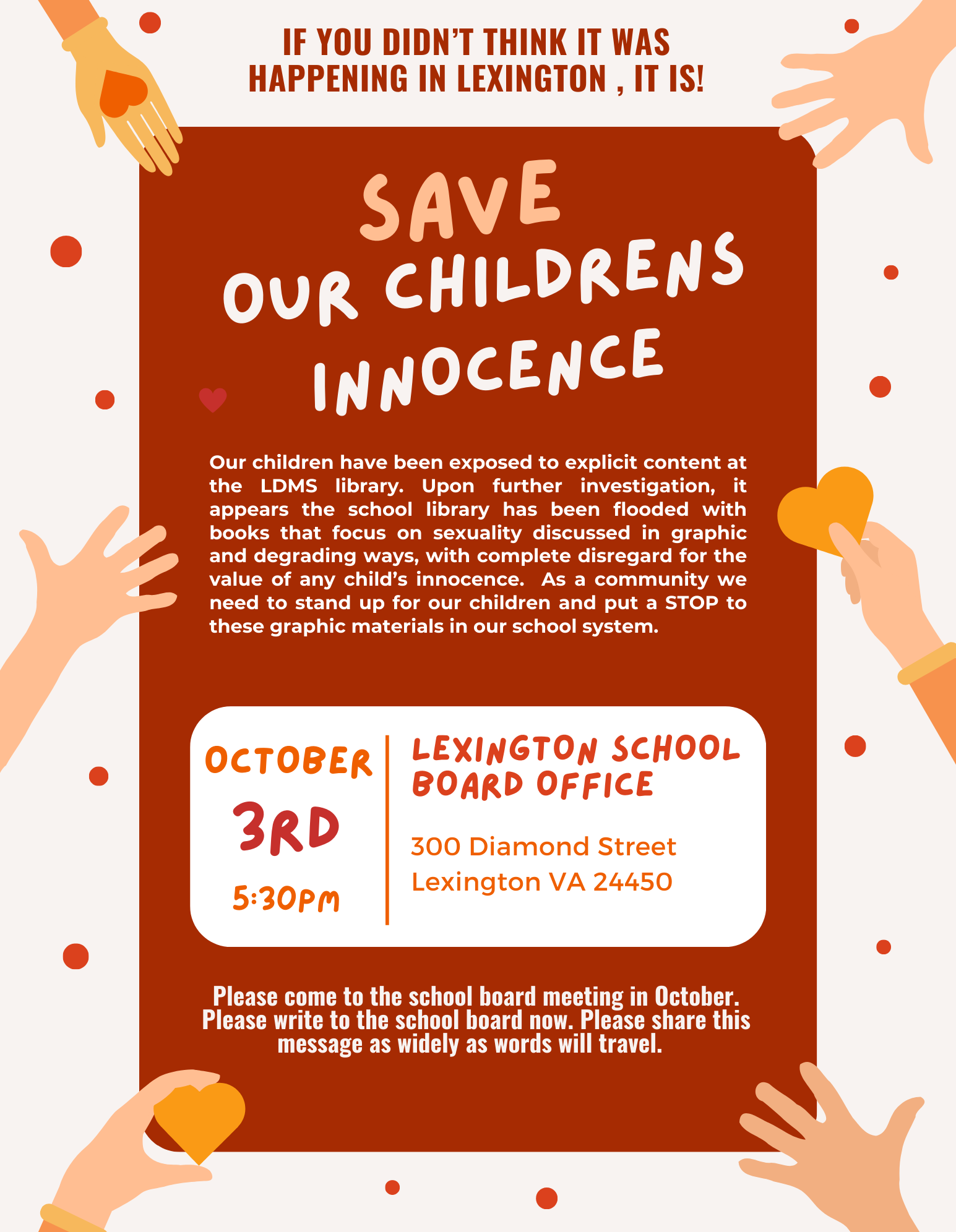

In their September 14 newsletter, the Rockbridge Area Republicans sent a flyer with the headline, “save our childrens innocence” [sic]. Copying language from Braman’s letter, it also called readers to attend the October 3 meeting.

Members of 50 Ways Rockbridge, a progressive organization with a mission “to build a more just and caring Rockbridge through community empowerment and political activism[,]” also began discussing the book removal last week.

A petition shared in their Facebook group on September 14 by Stephanie Wilkinson — known nationally for refusing service to White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders in 2018 — asks the school board “to abide by the Virginia Educational Association's standards of inclusivity and intellectual freedom in school library operations.”

Signers of the petition acknowledge their support of LCS librarians and “object in the strongest terms to any attempt by individuals to dictate changes to the collection based on personal or religious preferences.”

Other members of the 50 Ways Facebook group have written to local papers for support.

Chris Gavaler, an associate professor of English whose research at Washington and Lee University focuses on comics, shared the letters he wrote to the Lexington News-Gazette and the Rockbridge Advocate.

“The Lexington City School Board has begun banning books from its middle school library,” his letter to the Gazette began, “because a parent accused the school of ‘grooming’ children to be gay.”

“Parents should make decisions about their own children,” Gavaler continued, “not about other people’s children.”

“Perhaps a parent can sign a form barring their child from checking out material?” Gavaler suggested. “Or, if a parent doesn’t want their child to even be in the same room as a book, perhaps they can revoke their child’s access to the library entirely?”

“But it is unacceptable for a parent to make parental decisions for other children by demanding the removal of a book to satisfy their own preferences.”

Gavaler’s letter to the Rockbridge Advocate approached the topic from a different angle, stating that “[i]f you’re going to join a call to have a book removed from a school library, you should do your homework first. This means reading the book - all 305 pages, not just the two pages someone else photocopied and distributed in a letter of complaint[.]”

Gavaler then presented his summary of Kiss Number 8:

“It’s about a teen named Mads. She’s a Christian…Though she’s angry with her mother early on, by the end they have grown close, and they attend church together through every phase. Church is portrayed as an unquestioned positive constant in her life[,]” Gavaler continued.

Addressing the scene which Braman described as anti-Christian, Gavaler contended that only the novel’s villain, Cat, sexualized the sculpture of Jesus. Mads — the protagonist with whom Gavaler says readers identify — is disgusted by Cat’s views. “Cat is the novel’s foil, a model of how NOT to be,” Gavaler said.

Near the end of his letter to the Advocate, Gavaler claimed that “Cat, the villain, is irreligious, but Kiss Number 8 is not irreligious…People of faith should read and judge for themselves.”

A few members of the 50 Ways Facebook group referenced an alleged statement describing the removal of Kiss Number 8 sent from either the LCS superintendent or LDMS Principle, Abbott Keesee.

The Spectator reached out to Keesee, Braman, and the LDMS librarian for comment and clarification on September 14. At the time of publication, none of those individuals had responded. The Spectator did not find any official statement regarding the book’s removal online.